Omnipedia #29: UGI (Universal Generous Income), unravelling nudge theory, reacting to the "reaction economy", & more

Including: Hulk vs. the Leader, the glacial inevitability of Scots indy, trolly ontologies

More from the cosmos… It’s kinda political-theory-heavy this week (sorry, sometimes that’s what gathers up). But some sparkles too. If you like all this, please financially support independent writing and thinking, and hit the button below. Best, ad astra, PK

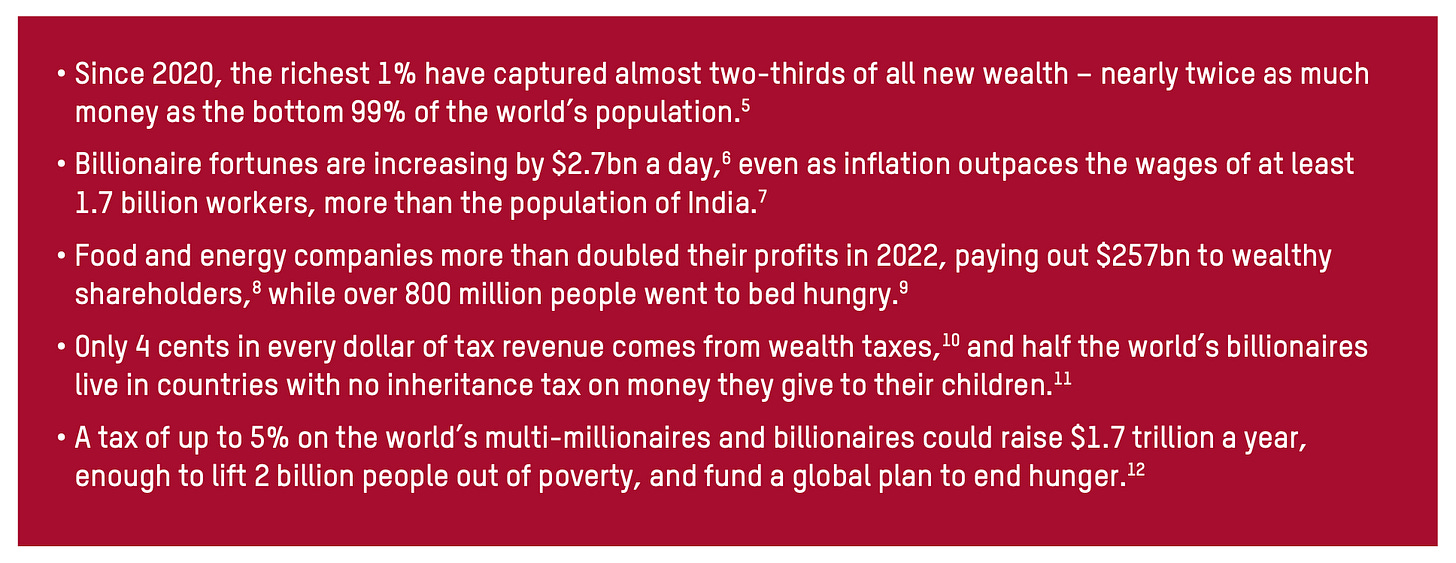

It’s brutal out here, right? “Survival of the richest”, as Oxfam say:

Statistics like that could easily tilt you into cigar-chomping revolutionary mode. But the rest of my attention span scans across radical technologies, and assumes their transforming force in the world (if harnessed in emancipatory social relations). So I often take succour from the techbros’ dawning realisation—that the vaulting, exponential future they seek will also have to provide some kind of human security.

Two decent men shooting the breeze on this are David Wood and Calum Chace, long-standing forecasters who run a calm podcast on all this called London Futures. I like the sequence in this episode (from 14.04) when Chace urges Rishi Sunak’s upcoming Tech Safety summit at Bletchley Park to consider the “economic singularity”—the idea that AI will technologically unemploy humans in an absolute way, not just open up new markets and careers.

Redistribution of the efficiency gains from the coffers of tech owners, and access to near-zero-cost services, implies… “Well, does it imply socialism, Calum?” asks the ever-elegant David Wood. Not quite, replies Calum - “though it might do”. They go on to redefine UBI as UGI - Universal Generous Income. This may not be on the Bletchley Park Summit agenda.

In an X’d response to this jaw-dropping plutocrat, we thank you for this Jack Kirby classic - The Leader:

The Leader clearly attacking Hulk as global proletarian. Yet both have been irradiated by the same technology. Accelerationism!

SINCE THE late 2000s, I’ve always hated nudge theory - the behavioural economics that assumes that we’re all Homer Simpsons, self-subverting our capacity for the crazy modern world as we are gripped by our mammalian biases and limitations. And thus needing our “choices” to be “architected” on our behalf, by managers or mandarins.

My decades of research and study of play tells me otherwise. Why remove Lisa Simpson - expressive, progressive, ethical, demonstrating her capability at all times - from her rightful perch in human nature? For more see my 2021 piece for Enough, titled (I’m a bit pleased with this) The Anti D’oh. (Below is a very clever abstraction, by Edinburgh graphics titan Stewart Bremner, of a certain cartoon character mentioned above.)

So it’s pleasing to read this Conversation UK piece about the promises and failures of nudge theory (and practice) over the last 15 years. An extract:

…A large amount of evidence questions whether nudges actually work at all.

After 15 years, plenty of nudge studies can now be assessed to get a better sense of whether this seemingly revolutionary idea really delivers…. Last year, one major meta-analysis reported finding no evidence of nudges working.

This was a big deal. And although the study had its own critics, who say it does not properly account for context, the analysis also supported previous evidence of publication bias, suggesting researchers have been cherry picking the “good” nudge studies to publish for years.

Nudge theory has also been undermined elsewhere by doubts raised around the usefulness of findings in behavioural science and psychology, as well as high-profile scandals involving allegations of data fabrication.

Critics of nudge theory have two key arguments. One is the notion that nudges have small (if any) effects on our behaviour, and are therefore ineffective policy tools.

Their second point is that nudge-based acts are open to being used by vested interests to distract policymakers and the public from actually effective solutions – that they put the emphasis on slight changes from individuals instead of more meaningful and effective systemic change.

For instance, nudges that encourage households to reduce their energy consumption may be considered a good idea. But what if this nudge also reduces the political will to pursue more effective (and expensive) policies, such as retrofitting homes or dramatically investing in sources of sustainable energy?

Even supporters of nudge theory have conceded that nudges may have overpromised in the past. A recent behavioural science “manifesto” argues that behavioural economists should “be humble” about limits of nudge theory. And in a 2021 updated edition of their famous book, Thaler and Sunstein – who never anticipated the phenomenal reach they achieved – argue that nudges are always part of the solution, but rarely the solution itself.

That point about nudges “reducing political will” seems the core objection here. Where Lisa’s idealism (or even Bart’s antic anarchism) is suppressed by the default assumption that Homer’s in charge of evolved human responses - our “predictable irrationality”, as another nudger Daniel Ariely once wrote. But isn’t political imagination about “unpredictable rationality”?

I HAVE been lost in the sociologist William Davies’ brilliant 2018 book Nervous States: How Feeling Took Over The World over the last few weeks. It’s been a research whetstone for one of my closing chapters in my beta-book SUPERPLAY (my The Play Ethic follow-up, after 20 years. And accessible, for a small fee, elsewhere on this writers’ site).

In correspondence, Will sent the below as an example of his current thinking:

I ALSO wrote this letter to the LRB earlier this year (March) about one of Will’s essays, where he developed one his themes from Nervous States, on the notion of the “reaction economy”. They considered printing it (but eventually didn’t). Still, I think it’s a good distillation of my own current thinking about political psychology, so here it is below:

William Davies’ excursus into the “reaction economy” (March 2nd) is intriguing. But neuroscience might have more to contribute to the argument than a pop-science sense of the “plasticity” and “mirroring” of brain activity. The contending schools in the current science-of-emotions debate - the constructionists allied with Lisa Feldman Barratt, and the affective neuroscience of the school of Jaak Panksepp - each cast a different light on the mass appetite for “reactive” media.

For one thing, the constructionists are urging us not to regard the facial expression of emotion as in any way an expression of natural kinds, ancestrally fixed in our brains. They push back against a predictable physiognomy of fear, anger, joy, sadness, etc, asserting that these are most likely rooted in Anglo-American-European cultural conventions. This implies that there might be some fuzziness in our determinations of what counts as a form of emotionally “authentic reaction” - even if that is itself a simulated act.

For another thing, the affective neuroscientists - who want to make contending claims that humans have evolved primary emotional systems, viscerally stimulable and shared with other mammals and animals - might possess some neurological research that can help Davies’ case for resistance.

Davies asks: How is it that children, youth and adults might “become comfortable with our own freedom, our own spontaneity, against the backdrop of surveillance capitalism, which is the real condition of the reaction economy”?

Panksepp identifies two of our involuntary emotional systems as “seeking” and “play”. And certainly the rise of a generally ludic and curiosity-driven culture, resting on game-like or interaction-based platforms and imaginariums, answers the question of the conditions in which we may fruitfully become “comfortable” with “freedom and spontaneity” (as I anticipated in my 2004 book, The Play Ethic).

The political and civic challenge is to imagine macro- and meso-structures which establish and sustain that “comfort”, in ways that commercial entertainment models hardly approach.

Macro, meaning shorter working weeks, and universal basic income and services: the political economy of “public luxury” as advocated by George Monbiot. Meso, meaning devices, software, organisations and physical buildings which are structured for playful, plural usage, rather than just retail or bureaucracy (both of which AI's algorithmic entities may be about to obliterate, in any case).

William is on the right track, in general. But I think the scientific map of what Marx once called our “species-being” is ramifying at pace. He should keep up with the brain science a little better than this, without becoming scientistic about any particular wave of it.

SCOTGEIST

As for Scots indy… surveys are telling us that people across these islands are “ambivalent” about the political Union of nations. And that demographics (the dying-off of older, indy-sceptical voters) and education (graduates tending to support indy in its liberal, progressive mode) makes a rise in polling numbers for independence inevitable [article and paper]…

…And you don’t need to tell Edinburgh’s skateboarders, as they carom through this year’s Edinburgh Festival, all about that.

One of the things Twitter/X is best at - a bunch of peers responding to a call-out to list the best restaurants in Glasgow. The instantiator, Mr Neil Scott, is to be relied upon…

And finally, the diary of my great friend, digital film auteur, and force-of-nature Glaswegian May Miles Thomas, who is making (in her usual fiercely independent way) a piece of ontological cinema about the life and times of a supermarket trolley, titled Milo In Real Life. A blog on how she’s doing with it, in all weathers.

OK, it ends here… for now. If you liked and value the above, then please financially support me with a paid subscription - the button is (and the options are ) below, love to all, PK